For the United States, July 4 is a holiday of fireworks and parties, an afternoon of family gatherings and barbecues. But for the French, what is the point of a barbecue without a Béchamel sauce? The French celebrate their nationwide festivities ten days later on July 14, more commonly known as Bastille Day. Bastille Day was supposed to signify the end of cruel monarchic rule, but like the effects of nationwide censorship, history repeated itself. This Old School Catalyst reporter was fortunate enough to be in Paris during the holiday and witness the irony of its democratic celebrations.

History

Bastille Day commemorates July 14, 1789, the anniversary of the fall of the Bastille prison in Paris. The medieval fortress was used from the 13th to the 18th centuries to house political prisoners or critics of the monarchy; among the famous intellectuals imprisoned was notable Enlightenment writer and philosopher Voltaire. By the 18th century, the prison was used sparingly and scheduled for demolition, but had become a symbol of the tyrannical rule of King Louis XVI, who had increased military presence in Paris in response to the lower classes’ request for a constitution and new social order.

On the morning of July 14, a mob of angry Parisians stormed the prison, seizing gun barrels and liberating its seven remaining prisoners. The storming and fall of the Bastille led to the French Revolution—a symbol of liberty and the power of the masses—and the execution of the royal family, followed by the rise of future emperor Napoleon Bonaparte.

As an American in Paris this summer, it was easy to spot parallels between Bastille Day and America’s Independence Day modern counterpart, No Kings Day. Like America’s Independence Day, the storming of the Bastille was supposed to mark a shift to democracy in France. But on a cold December day in 1804, Napoleon crowned himself emperor in the famed Notre-Dame in Paris. After all the bloodshed, France was under monarchical rule once again.

From 1814 to 1830—a period known as the Bourbon Restoration—Bourbon monarchs were restored to the throne after Napoleon was forced to abdicate. France became a constitutional monarchy, meaning the King retained sufficient power but was limited by a constitution and a bicameral legislature. The current Fifth Republic of France was not established until 1958.

Modern day Bastille Day, however, is less violent and more fun than its historic namesake.

Bals des Pompiers

The Paris Fire Brigade was decreed part of the French military in 1811 by Napoleon. Currently, the Paris Brigade, made up of 87,000 men and women, is the largest municipal urban fire service in Europe and third largest in the world. Bals de Pompiers, or Fireman’s Balls, are a century-long tradition wherein firehouses across all twenty districts of Paris turn into packed, free-to-access nightclubs on the evening of July 13, acting as free hotspots of music and dancing across Paris. The tradition began accidentally in 1937, when residents followed firefighters on their way back from marching in the Fête Nationale military parade. The firefighters opened the gates to the station house and invited citizens in for an impromptu dance party.

By 10:30 p.m. at the Saint Germain Caserne Colombier on Rue du Vieux Colombier, lines wrapped around three city blocks. American songs like David Guetta and Sia’s “Titanium” could be heard coming from inside the fire station. It was a scene not unlike Miami’s own nightlife—girls stood in line dressed in mini denim skirts and black leather boots and one couple from Chicago stood in line for two and a half hours before losing patience. Young people were walking around with open bottles of beer or canned alcoholic drinks, a shock to an American from the land of open container laws.

One girl waiting in line with blown-out blonde hair and a sparkling, tight blue dress had come from Australia and traveled through the Netherlands before arriving in Paris, along with a friend in an orange halter dress who had come from England.

After a little under three hours, this writer and her posse decided to call it quits at 1:15 a.m. Even though this American was unable to dance inside, the electric atmosphere on a beautiful Parisian night was enough. On the walk back to the hotel, restaurants were packed with patrons ordering salmon, steak and champagne to welcome the morning of Bastille Day.

Bastille Day Military Parade and Flyover

At 10 a.m. on Bastille Day, the Arc De Triomphe and the Champs Elysees were surrounded by red, white and blue flags and soldiers in military regalia. Bugles and trumpets played as the President of the Republic resided over the festivities. The themes of the Fête Nationale parade included strategic solidarity with allies, the commitment of young people and 100-year anniversary commemorations of a few military and patriotic organizations.

Seven thousand women and men from the military, 200 Garde Republicaine horses and more than 4,000 Republican Guard soldiers marched on foot past crowds seated in temporary bleachers along the Champs, as seen from the hotel television.

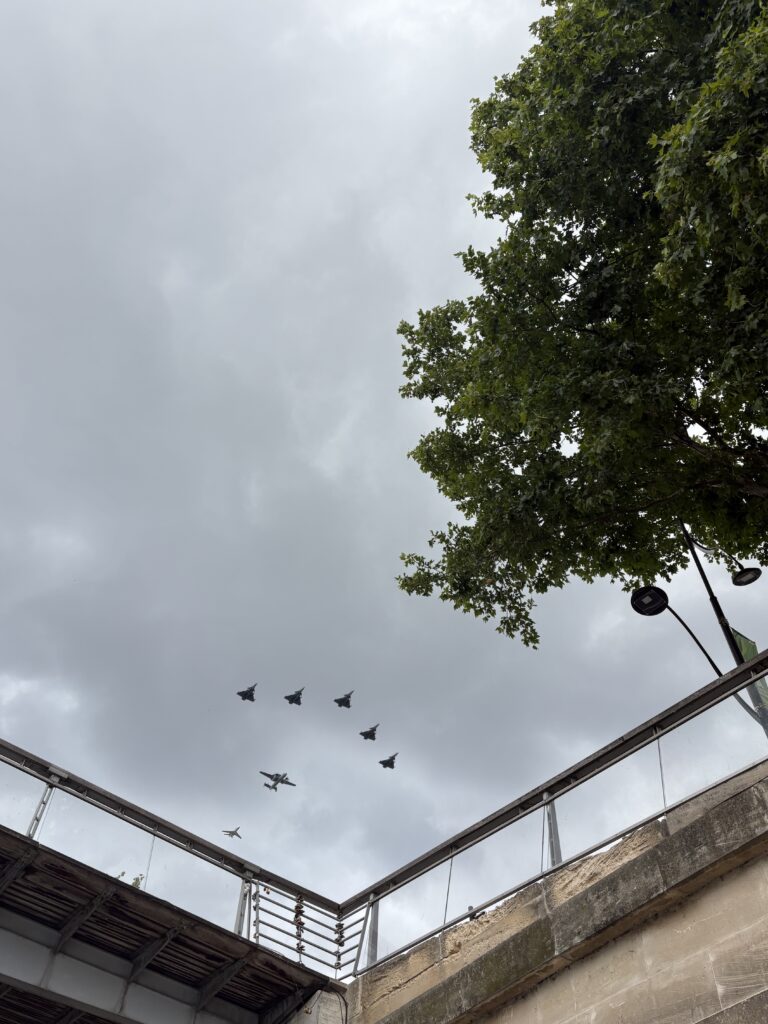

At 9:30 a.m. this traveler set out to see the parade. Walking along the Seine, the streets were barricaded and police officers were blocking the way to the Champs. What would normally be a sleepy Parisian morning was anything but, hopping with hundreds of people walking along the river like the New York City marathon. The city was alive and buzzing with activity. A loud whoosh was heard overhead as the flyover had commenced.

At around 10:25 a.m., 39 military aircrafts from the French Navy and Air Force flew together over the city. The flyover is a symbol of national identity and military power. The flyover planes are typically three to 20 meters apart from each other, or nine feet. The helicopters and planes, Rafale Fighters and Reaper Drones, soared over the city of lights as crowds of people cheered and pointed from below.

Then nine Alpha Jets from the Patrouille de France, the elite aerobatic team famous for their tightly synchronized flight patterns, painted the sky in strokes of red, white and blue that could be seen from anywhere in the city. The loud roar of the planes intensified as they whizzed by overhead in perfect synchrony.

Fireworks

On Bastille Day, the Louvre is free for all. The line only lasted about an hour and after scarfing down salads in line, this art lover was graced with Davids and Delacroix. In the evening, the city puts on a free outdoor music concert on the Champs-De-Mars, near the Eiffel Tower. Tired of striking out on Bastille Day festivities, this reporter and her family enjoyed a lovely dinner in Saint Germain, a part of the city that is always celebrating. One would think it was Bastille Day every night. After the late dinner, the group wandered to the Seine where hoards of people were looking for a spot to stand and watch the fireworks.

Bastille Day fireworks have been a tradition since 1888 and are launched from the Eiffel Tower. The show not only had fireworks, but drones that created brightly colored birds and other fun creatures.

To celebrate such a nationalistic holiday as a foreigner was a strange but joyful experience. The dark history of Bastille Day is no match to the glorious and fabulous ways it is celebrated. Even though France would see a monarchy again, that is not why Bastille Day is remembered. May it be a lesson that democracy and liberty will prevail, no matter what cloud covers a country’s current political climate.