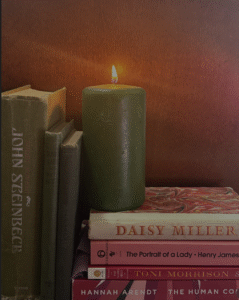

The number of books challenged in public libraries across the country has sharply increased since 2021. Books discussing race, gender or sexuality have been targeted and labeled “obscene” by Republican lawmakers and right-wing activist organizations such as Moms for Liberty, founded in Florida. In the midst of these bans, public librarians who have pushed back against government overreach in education have been fired or publicly smeared. In a country where librarians were once seen as everyday superheroes of public service, it is vital to know what has caused this shift towards demonization.

Kim A. Snyder explores this political phenomenon in her new film, “The Librarians,” which won the 2025 Sarasota Film Festival’s award for Best Documentary Feature earlier this month after screening on the New College campus. Snyder also directed and co-produced Death by Numbers, which earned a 2025 Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary Short Film. “The Librarians” follows the stories of multiple librarians from Florida and Texas—including Manatee and Clay counties—who have lost their jobs after refusing to comply with book ban legislation. According to a November 2024 PEN America report, “Banned in the USA: Beyond the Shelves,” Florida ranked first for the most book bans for two years running, amounting to more than half of all bans nationwide. Iowa and Texas hold second and third place.

“It was a pleasure to burn,” Kim A. Snyder’s film begins, quoting Ray Bradbury’s “Fahrenheit 451,” a 1953 dystopian novel set in a world where books are banned and burned. “It was a special pleasure to see things eaten, to see them blackened and changed.” All eyes were glued to the screen in the darkness of Sainer Auditorium.

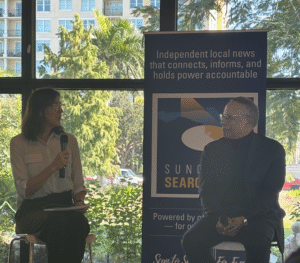

Old School Catalyst had the opportunity to speak with Snyder about the documentary and the significance of showcasing it at New College.

“The Librarians” explores the sudden emergence of book ban legislation in conservative politics and how these bans have affected the careers and lives of public school librarians. Why did you choose this topic to center your film around?

I chose this topic three and a half years ago, prompted by learning about the Krause List—which was a list of 850 books issued by Texas State Representative Matt Krause—that was asking schools to look through their libraries and remove these books. The books were almost exclusively about race, gender and sexuality. Then I learned about a small group of librarians who were calling themselves the Freadom Fighters and were speaking out about [the Krause List]. That was interesting to me. I had the instinct that this was potentially the beginning of a movement to bravely defend our rights, being led by librarians. I quickly learned that although people were sharing a lot about book banning . . . I think this film opens people’s eyes to the extent of the siege, of an attack on our librarians. The librarians themselves, not just the libraries. It was the people that attracted me to the story. I always like to tell stories that have a real human element.

Your film won the top documentary prize after screening on the New College campus. For the past three years, New College has been the target of the Florida government’s conservative takeover of higher education—which included firing librarian Helene Gold, but also a massive book purge. What did screening at this location mean to you?

After seeing the image of that dumpster, which is undeniable… I think we all have to make decisions right now about whether we stay in Florida or leave Florida. We’re all making decisions about what we want to do, how we want to speak out about preserving democracy and our rights and what resistance looks like. For me, I ultimately decided that to screen at New College in itself was my own way to be part of resistance rather than not. I’d rather be in spaces where we need to raise awareness about things that are an attack on our First Amendment rights and our freedom to read. We need to highlight that. What better way to do it than show my film about book banning? So I was pleased.

I commend the festival for embracing films like mine, showing films like mine, because they didn’t have to. They could’ve cowered in some way. But I commend them because, ultimately, I do want to show the film in the service of civic dialogue. That’s what happened that night. There were a lot of people from Sarasota who showed up in that space. They knew what had happened. They came because they wanted to see a film that exposed this. I knew what it meant to me, that it was significant, and I think for a lot of people in the audience, that was not lost on them. I have no idea what it means on behalf of the college. I couldn’t speak to that.

On a personal level, did meeting librarians who have lost their jobs or had their reputation damaged because of the political climate impact you?

Absolutely. In fact, I had the pleasure of meeting the former librarian from New College. That was really interesting in terms of the local tie-in, that ironically, my film was going to play on the campus of New College. I had met and spoken to Helene Gold, and then later learned that she lost her job. It impacted me a lot to understand the courage and the commitment of these librarians.

Something that really stuck with me while watching the documentary: the claim that “pornography” can be found in the children’s public library is often used to justify book bans, despite being unproven. Why do you think this absurd rhetoric is being used by politicians?

That’s a really good question. I believe that in order to have any grounds to counter the idea that [book banning] is against constitutional rights, there’s an attempt to use state penal code laws. In order to do that, you’d have to say that [the books contain] pornography. That’s one answer. I also think that one person’s definition of pornography does not make it so. So, for example, there’s something many librarians learn in their training called the Miller Test. The Miller Test is a legal basis for determining if a book is actually obscene or pornographic. There’s a criterion. None of these books, according to all kinds of librarians, meet the Miller Test. They are using it in a way no trained librarian I’ve met agrees with. Not one has said anything meets the criterion of pornography . . . often used to speak about literature like Toni Morrison and literature that sometimes depicts sexual assault . . . [Calling these books ‘porn’] is offensive to many people, including me.

Not everyone has to check it out, it’s voluntary. But the idea that 16, 17, 18-year-olds that have the right to do all kinds of things, or an 18-year-old who will be able to buy a gun in Florida, can’t have the freedom to explore that kind of literature. . . . I’ve met high schoolers in Texas who will say, ‘You know, look, sometimes we learn what consent looks like and doesn’t look like through reading such literature.’ If you look at Toni Morrison’s book and read about the rape of a person of color and call that pornography, something’s wrong with you. If you find that titillating, that’s messed up.

I also think that it’s clearly an attack on queer young adult literature, no question. Any kind of attraction that would be okay in heterosexual context or anything that’s against the Bible is considered porn by many who have more of a white, Christian supremacy agenda. That’s how they’ve used it. That’s not how I think the majority of America understands and defines porn.

Note to readers: In Florida, the Miller Test would potentially be overridden by HB 1539, a bill currently being considered by the Florida House. Beyond the criterion of obscenity, this bill would eliminate “literary value” for judging challenged books: “A board may not consider potential literary, artistic, political, or scientific value as a basis for retaining the material if it contains material harmful to minors.”

Why do people believe it?

God knows why people are believing it. Look, I made films about gun violence and mass shootings like Newtown, where lots of people say it didn’t happen. There are people who believe Hillary Clinton is running underground pedophile rings. Whether it be fringe QAnon-type stuff or otherwise, the sad thing I learned is that naysayers are not confined to a few people. There was a huge swath of people who didn’t believe [the Sandy Hook shooting] happened. I think somehow it’s the same phenomenon—a huge swath of people who do believe there’s pornography [in libraries]. But again, it also depends on how you define it.

It can be easy, especially in more liberal states, for people to ignore what’s happening in conservative landscapes such as Florida or Texas. Why should Americans, on a broader scale, care about what legislation passes in a state hundreds of miles away from them?

We started the film in Texas because there were such egregious things happening there. One of the reasons we broadened it to go to Florida, and then even New Jersey, was so people couldn’t say, ‘Oh, that’s just crazy Florida. We don’t have to worry about that here.’ It is widespread. Yes, I definitely think you should care about what’s happening in Florida and Texas, but more importantly, if you think it’s isolated, you’re sadly mistaken. The larger implication of what this means as an affront to a democracy is the hallmark of every totalitarian trend’s beginning. That’s why I used historic context in the film. That’s why it’s so important to point out McCarthyism and [Nazi] Germany. There are so many other references I could’ve used if I wanted to. I could’ve pointed to the Cultural Revolution in China. I could’ve pointed to Cambodia. It often starts as an attack on education, elite universities. . . These are the hallmarks. New College is a very specific, unique kind of situation, but as we all know, we’re seeing higher education being pressured to abolish all kinds of diversity and infringements on all kinds of freedoms.

People should care about other states, people should care about their own state and the legislation, and people should speak up about these things. In the case of filming in New Jersey, we see regular, patriotic Americans going out of their way to do things that actually make a difference, like Martha [Hickson] getting the Freedom to Read Act [signed] or Suzette [Baker] in Texas getting [Llano County] libraries to stay open. I do think that grassroots organization and bringing issues to the town hall space of civil dialogue can matter, and that’s what we’re trying to do with this film. People have to speak up, resist, not lose hope, not be apathetic. It’s gonna take everybody.