There’s a well-known stereotype among LGBTQ+ people of the young person born and raised in a rural or conservative area hostile to their identity who, as they come of age, breaks free and moves away to a flourishing urban “gayborhood” somewhere across state lines. But an estimated three million LGBTQ+ people currently live in rural America. What about the ones who never leave? Even more—what about the ones who dedicate their careers and their art to dissecting and memorializing their home state?

Kristen Arnett is a queer author who grew up and continues to live in Orlando, Florida. She dropped out of the University of Florida after one semester when she discovered she was pregnant, then spent several years balancing raising her young son, taking night classes, working during the day at myriad public and academic libraries and discovering her own queer identity. She wrote her debut novel, Mostly Dead Things (2019), as she was finishing her MA degree in Library and Information Science. Her second novel, With Teeth (2021), followed closely behind. All of her works tell the stories of queer women navigating life in Florida, often with an undercurrent of absurdity—political, environmental and cultural—that comes with the territory.

Arnett’s latest novel, Stop Me if You’ve Heard This One (2025), is a slice of life dramedy about Cherry, a lesbian professional clown living in Central Florida, trying to answer the question: how does one make meaningful art in an environment that fundamentally misunderstands you? One where you struggle to understand yourself?

In a far-ranging Zoom interview, Arnett answered these questions and more for Old School Catalyst.

What has growing up in Florida been like for you?

There’s this idea that living in one place your whole life seems like a monotony of a same lived experience. I’m going to be 45 this year, and if anything I feel like I’ve lived many disparate experiences inside of this one space.

I grew up a 10-minute drive from where I live right now. My family had no money, we were pretty poor, and the house I was in was across the street from what was at the time a topless bar. We actually weren’t supposed to look out the windows at night because you could see the women out back talking to people or taking smoke breaks. And on the other side of that, there had been a wastewater treatment plant, and so the air always smelled like that mix of waste. Now, there are all of these really expensive homes pushed up against it. So I can’t talk about “living in the same place I grew up in,” because that place doesn’t really exist anymore.

In my memory of it, there’s this idea of teeming, fecund life, a very feral thing. There were always creatures around, possums biting into things. I think a lot of times about the feral where it meets the humanness of spaces, how those things butt heads and intersect. My experience of living here is one where I always make the joke, “I’ll stop writing about Florida when I’m bored,” and I’m never bored here.

As you were growing up, when did you first develop an interest in writing, or know that it was something you wanted to do seriously?

It took me a long time to realize that it was something I could do seriously. It’s something I always did, but I treated it as something very private for myself. I wasn’t someone who ever journaled or kept diaries, and part of that was being very closeted and afraid of what someone might read about me. But also I think the bigger answer to that, is that I was scared of what I would see of myself if I wrote into those spaces. And so I think my coming out process really coincided with my writing, because once I felt that freedom. . . my writing really flourished in a way that I think it couldn’t have before.

But I was always writing little stories. I grew up very Evangelical and we went to church every other day. . .We would have these church bulletins where you’re supposed to write thoughts on the sermon or things like that, but I would write small stories. Like me writing myself into The Baby-Sitters Club books, which was also me being incredibly gay.

My stories were always stories that took place in Florida. Florida was so confusing to me, but it was also what I knew. There are very bizarre things happening all the time, and so I think writing was a way to maybe process or make sense of them in my brain. But it took me a long time to think that this was something I wanted to do as a career—it took me a long time to even tell people that I was a writer. . . You have to say to yourself first, “I am a writer,” before you can say it out loud.

[In my early 30s] I was going to this school that I ended up working in the library of. It was a very expensive private college that I had a scholarship to go to at night, and they had a thing they used to do called “Winter with the Writers,” where they would have really famous authors come out, and you could submit work to be in a workshop with them. I remember thinking that I didn’t want to take up space from a real writer, but my professors really encouraged me to do it. I ended up applying and I got in, and it was my first time being in a workshop space where other people read my work. It was like a light bulb went off in my head. It wasn’t like people told me my work was good, it was like people saw what I was trying to do and we were in conversation together.

I envisioned this—I think we all do this—this imaginary person who, as soon as I would say I was a writer, would pop up and would say, “Well, what have you actually done? What have you published?” The reality is that that’s not how it works at all. You put up a lot of walls to prevent yourself from doing the things that you want to do. I put those things in place for myself too.

You’ve said all of your writing takes place in Florida. What about Florida feels worth writing about?

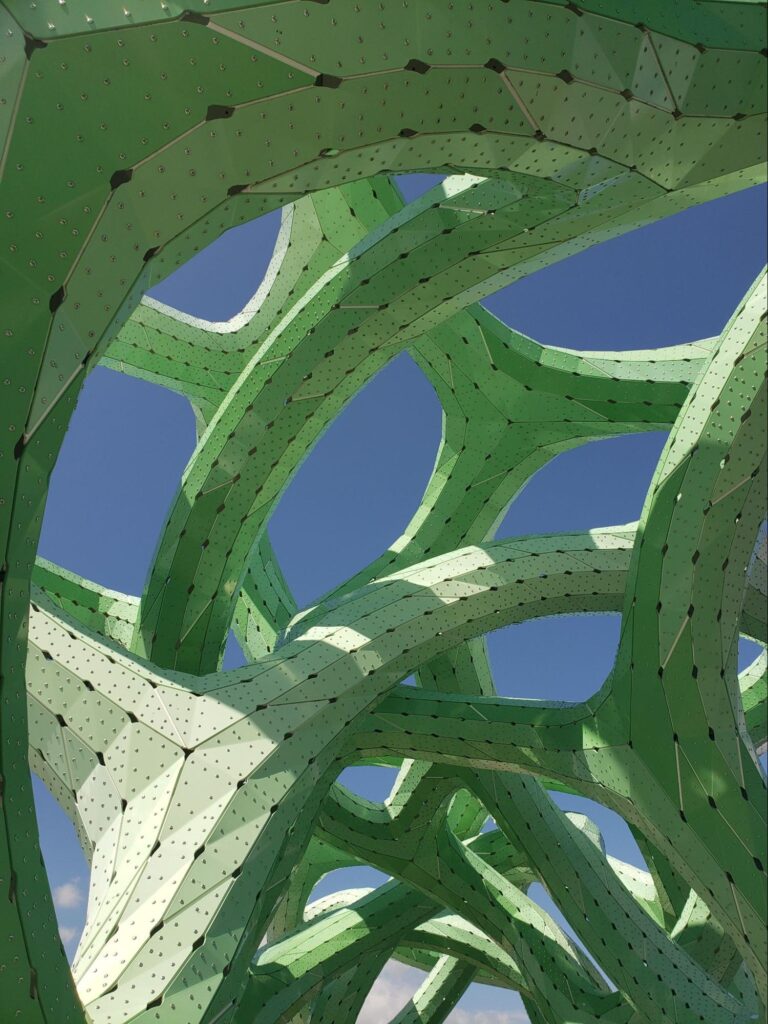

So much of the natural environment here, regardless of where you are in the state, refuses to not be discussed. It kind of creeps its way into everything we do as we move around on a daily basis. There’s something very fascinating and fleshy to me…I think of Florida as a creature. It’s not just outside your window, it’s always got its tendrils underneath the bottom of the door.

Some of it is that you can’t be bored here, but some of it is that Florida doesn’t let you forget about it. We’re so dependent here on what’s going on with the weather, what time of year it is, the tourism economy, who’s coming in, who’s going out, what job and work situations look like in relation to that. Our government is f—ing wacko and it’s pretty much always been that way. All of these things make it so that there’s always something to think and talk about.

We are in a space that is different from anywhere else. Other states have their own stuff too, but we just have so much of it. It’s a space where you can be writing about the beach, or writing about animals or about springs or about a hurricane, or about a flood, or you could be writing about weird government stuff happening on top of that, or small business or theme parks. All of these things all sit inside this small-a— space [of Central Florida], and that’s one small portion of the space that we’re in. It’s the too-muchness—it feels like a sort of caricature.

Have you ever entertained the idea of leaving Florida, or do you feel comfortable in thinking you’re always going to be here?

As a person, I don’t want to limit myself. I’m also married to another writer, so I want to be open to the idea of having different spaces. The longest I’ve ever been out of Florida was when I had a residency in Las Vegas. I was out there for six months for a fellowship. I very quickly knew that I don’t ever want to move to the desert; I literally had a nosebleed every day. I’m like a swamp creature.

I’m also very interested in meeting people and trying different things, and so I’m not adverse to going away but then coming back. I always want Florida to be home base, is what I’ve decided.

You’ve used the word “caricature” to talk about Florida as a subject. Another Florida-based author I interviewed talked to me about the Florida Man trope, or the perception of Florida as the butt of the joke for people outside of the state. Has Florida earned that reputation?

It would be a mistake for myself to say it’s totally one or the other. We have the Sunshine Laws here, which mean that when weird s— happens, unlike other places that have laws in place to protect individuals so that things don’t immediately go to newspapers, we have the opposite of that in Florida. Any and everything goes immediately into a news aggregator. So people get to see somebody throwing a live baby gator into a Wendy’s drive-thru window, like immediately.

Is that a real example, or did you just make that up? I genuinely can’t tell.

It was real, actually. I know one that is like, “Naked Florida man breaks into Ford dealership, steals a truck.” But instead of there being laws in place to protect these citizens so their information is vetted, this state pushes all of it immediately so that anyone can post about it or write about it or have it as news. There are many such cases of ‘Florida Man’ happening in other states, they just have better protections in place so people don’t see it with the intensity that Floridians have.

But also, let’s be so for real—there’s a bunch of weird people that live in Florida. We have an insane government, but we’re also a place where weirdos come because they want to come down and act weird in different ways. We’re a retirement destination. . . and we have a climate that facilitates hurricanes where it feels like everyone’s going to die, and when you’re in a life or death situation it makes people make interesting choices, I think. We also have cultures of tourism pockets, so it’s a lot of drinking and drugs and different kinds of situations.

I think Florida Man is something people in other states try to use to feel better about themselves, or to write off an entire population, which I think is inhumane. It’s a thing people use so they don’t have to have empathy or care for a people and a place. We’re always writing about Florida Man, but I also feel like I’m constantly trying to write through and against Florida Man.

In Stop Me if You’ve Heard This One, there’s a protest that takes place at a children’s fair that Cherry is working at, because there was a drag artist reading to children. The moments right after the protest, as Cherry returns to the fair, the whole event has been tainted for her—there’s something surreal and darkly funny about it. I’m wondering if you can say more about finding humor in our precarious situation here in Florida.

To me, this scene is funny, but it’s also about the constant expectation that you’re supposed to experience a horrible trauma and then immediately move on from it. That is an awful thing, but it’s also so absurd that it’s very humorous. Like oh, there was just somebody with a gun over here but now we’re going to move on? There’s face-painting going on, and we’re going to blow up a balloon?

That’s a part of being human, to me. Even if we’re going through terrible grief or trauma, it’s not like there aren’t moments or breaks where other feelings are happening. Moments of boredom and apathy happen in the middle of all that s— too, or moments of ridiculousness or humor or intense empathy and love and care. We still push through and are living small lives. People sometimes ask, “How are you living in Florida every day as a gay person and not living in a bunker or looking out with a shotgun?” But that’s not how people live. It’s not a constant barrage of s—, it’s just moments where s— is also part of your lived experience.

We’ve hit the part of the interview where I want to start asking you about clowns. Have you always liked clowns?

I haven’t had strong feelings one way or another. I’ve never been scared of clowns. Growing up, one of my first memories was a little clown doll I had that I named Mustard. I was a child of the ’80s, so I grew up at a time where there were clowns at parties. I am a huge Stephen King fan, so of course I read It and I have a clear idea of why people would be scared of them. Clowns are like a thing of too-muchness; they can twist the wheel from extremely funny to extremely scary very easily. There’s too much of a voice, very colorful clothes that don’t look right because they are exaggerated. . . But what is more the icon of humor than a clown?

There’s a way that the lexicon is working now and language is working where people are saying “clown” to denote a lot of things. “Your boyfriend’s a clown, the president’s a clown, you’re clowning on people.” This is very fascinating to me, so I got more interested in the construct of a clown and how clowns work or how they don’t work. I’m also in an entertainment space in Orlando where there are clowns here constantly working. NPR covered it maybe two years ago, but we have the World Clown Association that meets here. They come here to a convention center, and people are serious. They’re protective of each other, and they treat it as art. It was like a task for myself: can I write a book about something that people hate and make them laugh?

It’s the most fun I’ve ever had writing a project. I could feel Cherry tumbling through the book as I was working out her story. Everything became about clowns for me. What isn’t clowning? And I became so annoying. I would be a really annoying person at home with my wife or at dinner talking about clowns. I got obsessive over it, and that told me that it needed to be a novel.

Obsessive in the same way with writing about Florida, that too-muchness?

Yes. For me, I need to have two beers and really bother somebody about something, and then I know it’s a book.

I would argue that clowns are making a comeback in certain niche, Gen Z queer spaces in a more positive way. Do you have other thoughts about the different incarnations clowns take in our culture, and do you see a throughline of queerness?

In Orlando, we have something called Dyke Nite which is mostly people who are Gen Z, so I definitely feel like a queer elder in those spaces. But they had an event called “Fool for Love” in February, and it was a clown party. It was like 200 queer people all dressed as clowns, and it was a very sexy night. So yes, it’s very fascinating.

I think there’s something to be said about a crossover with drag, the caricature and idea of a thing. When I was writing Bunko, Cherry’s clown persona, I was specific in writing that the clown is gendered male while she’s occupying his persona. It’s like a form of drag. I also think the idea of queerness is like, how you need to code-switch in different spaces, who do you need to behave as right now? And with other queer people, how do you act queer for one person versus with different kinds of people?

I thought of queerness constantly as I was writing that. I think the idea of how you identify with gender, with sexuality, how you look and feel moving through a space, who you might encounter and how you might perform to make people love you more. These things all made total sense to me in terms of how a clown might work.

Considering everything we’ve talked about—humor, grief, queerness, Florida—do you have advice to offer any young queer artists living in Florida, growing up in your same situation and navigating our current political landscape?

Don’t limit yourself and your art based on what’s happening around you. We’re our own harshest critics of our own art. We find reasons to stop ourselves from making something. “People won’t like that,” or ”Somebody might be angry with me,” or ”This isn’t something that anybody wants.” And we stop ourselves before we can get started.

We are first and foremost making art for ourselves—it can be writing but it can be any other artistic practice. I think all of these things sit and hold hands together: clowning, painting, sculpture, comedy, vocals, dance, they all start with this idea of “I want to make a thing,” and you’re making it for yourself first and foremost. And if you don’t make that thing, you’re not having a valuable relationship with yourself.

Even if it’s just writing yourself into The Baby-Sitters Club?

Exactly.