For two years in a row, Florida has led the nation in banning books, accounting for approximately half of all book bans in the country during the 2023 – 2024 school year. Why book bans are making a comeback in the 2020s is a complicated question, but in Florida, there’s one law that many anti-censorship advocates point to as foundational: HB 1069.

Passed in 2023, HB 1069 is similar to other Florida laws that mandate what classroom materials can be offered and what curricula can be taught in public schools, with a focus on restricting access to topics of race, human sexuality and gender identity. Well-known examples are the “Don’t Say Gay” law and the Stop WOKE Act. And like these two pieces of legislation, HB 1069 has also come under fire for violating the Constitution.

On Aug. 13, U.S. District Judge Carlos Mendoza overturned a large part of the law after ruling that it violated students’ First Amendment rights. On Sept. 10 Gov. Ron DeSantis and the State of Florida filed a notice to appeal the ruling, which could take this case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Old School Catalyst offers below a full breakdown of HB 1069, how it works, why people take issue with it and what the future of book banning in Florida might be.

What does HB 1069 say?

HB 1069 mandates the following in public K-12 schools:

- Every school must uphold the policy that “a person’s sex is an immutable biological trait and that it is false to ascribe to a person a pronoun that does not correspond to such person’s sex.”

- Employees cannot provide students with their “preferred personal title or pronouns” if they do not correspond to the student’s biological sex.

- Employees cannot ask students for their “preferred personal title or pronouns.”

- Instruction about sexual orientation or gender identity can only occur in grades 9 through 12 if it is “age-appropriate or developmentally appropriate for students in accordance with state standards.” This mandate also applies to charter schools.

- Health education in grades 9 through 12 must “teach abstinence from sexual activity outside of marriage as the expected standard for all school-age students while teaching the benefits of monogamous heterosexual marriage.”

Along with this, HB 1069 mandates that all districts create a formal process for citizens to object to library books in K-12 schools. A book must be removed from schools if a community member objects to it with any of the following rationale:

- It is deemed “pornographic”

- It “depicts or describes sexual conduct” (a phrase with no specific parameters defined by state law)

- It is “not suited to student needs and their ability to comprehend the material present”

- It is “inappropriate for the grade level and age group”

Once objected to, the school must remove the book(s) within five days and they must remain unavailable unless the objection is resolved.

To potentially “resolve” objections, HB 1069 calls for each district to create public committees to review books that have been objected to. These volunteer committees are made up of parents of students at the school where the objection has been filed. They read the books in their entirety and decide among themselves whether they are appropriate for a certain grade level. Once these committees reach a verdict, the findings are brought to their districts’ school boards.

This process can often take several months.

How have these mandates caused books to be banned?

HB 1069 did not kick start the current wave of book bans in Florida. In-state and across the country, organizations such as PEN America have been documenting these bans in earnest since 2021.

The current book banning movement is credited primarily to Moms for Liberty, a far-right political organization that advocates in opposition to public health regulations and LGBTQ+ and racially inclusive school curricula, and BookLooks, the now-defunct website featuring a content rating system that warns against “gender ideology,” “profanity” and “extreme/frequent hate” in books.

Stephana Ferrell, who is Director of Research & Insight for the Florida Freedom to Read Project and a public school parent from Orange County, recalled the first instance of book banning she witnessed in October 2021, after a known affiliate of the Proud Boys attended a school board meeting to object to a book. The board responded positively, saying that the book in question would be immediately removed.

“That night I went home wondering, what just happened?” Ferrell told Old School Catalyst. “I thought, ‘Wow, that is a lot. Not familiar with the book. . . I don’t know what the book’s about.’ So I read the book because I didn’t want to form an opinion of it just based on the excerpt.”

Typically, when a person makes a public objection to a book by attending a school board meeting to voice their concerns, they will read a few sentences or a paragraph from the text that they find personally objectionable.

While HB 1069 allows for books to be removed immediately if they are objected to on the grounds of containing depictions or descriptions of sexual content, there is also the Miller Test, a Supreme Court standard for defining obscenity in books that has been in place since 1973. The third prong of the Miller Test rules that the entire text of a book, and its “literary, artistic, political or scientific value” must be taken into account before it is banned.

“I honestly breezed over the section that they [the objector] had read aloud and that had caused the issue, not realizing it,” Ferrell continued. “Because what happened right after it was something that I connected with about setting boundaries in a loving relationship and having those boundaries respected. To me, that’s so important for teenage students to learn.”

One month after Ferrell witnessed this initial book banning, the Florida Freedom to Read Project noticed similar objections taking place at school board meetings across the state.

“It seems so small now, but I think we finished that year with around 500 censorship attempts that we had tracked, and a lot of them were still pending,” she said. “But now we’re in the thousands every single year.”

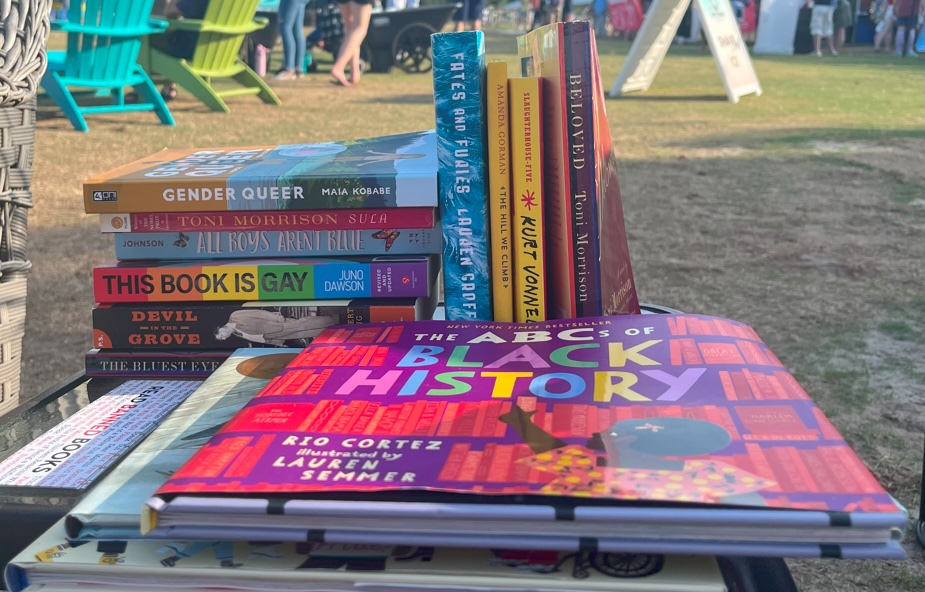

Prior to HB 1069, books that were banned were targeted predominantly for aligning with diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) concepts.

“Complaints about diversity and inclusion efforts have accompanied calls to remove books with protagonists of color, and numerous banned books have been targeted for simply featuring LGBTQ+ characters,” PEN America reported in 2022 about book removals from July 2021 to March 2022. “Nonfiction histories of civil rights movements and biographies of people of color have been swept up in these campaigns.”

Ferrell noted that, once HB 1069 was law, there was a notable uptick in the number of book bans in Florida, and that the types of books being banned expanded as well. Banned books began to include titles by authors such as Toni Morrison, George R. R. Martin, John Green and Kurt Vonnegut, books featuring depictions of Michelangelo’s David sculpture, children’s picture books, graphic adaptations of Anne Frank’s diary and in one Florida county, the Merriam-Webster dictionary.

“We saw in certain areas that there were groups that were able to utilize their newfound empowerment to file 60 objections at a time, overwhelming the districts,” Ferrell said. “[In some cases] they bypassed the review process, and now they’re just looking at the objection forms and excerpts out of context and they’re making decisions [based on that].”

What problems were found with HB 1069?

U.S. District Judge Carlos Mendoza ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in a recent book banning lawsuit that explicitly names HB 1069, where he wrote that the law is “overbroad” and “unconstitutional,” and that it goes beyond what the Miller Test establishes.

“Here, neither a prohibition on content that ‘describes sexual conduct’ nor that which is allegedly ‘pornographic’ takes the third Miller prong into account,” Judge Mendoza wrote, according to reporting by BookRiot. “Both prohibitions lack the specificity required in identifying obscene material. Given that obscene material as to minors is already prohibited under Florida law, these terms must, therefore, target non-obscene material.”

Even before this ruling, parents like Nancy Tray from St. Johns County have argued that HB 1069 and its language about “pornography” in books in schools is intentionally vague and misleading.

“If these were pornography, then Barnes & Noble would have to treat them as pornography, and Amazon would have to treat them as pornography,” Tray told Old School Catalyst, referring to the books banned in her county under HB 1069. “We know pornography when we see it, and they’re not pornography at all. There’s a lot of value in the books that are banned in my county and in other counties around Florida as well.”

“Young people, as they head into adolescence, are naturally going to have questions about sexual situations,” Ferrell explained when asked about sexual content in books. “But books are written to address those topics in age-appropriate ways with young people in mind. There is a First Amendment right even for our youngest citizens to be able to access information that they need, and that can help inform them. You cannot protect innocence with ignorance.

“We’ve seen nonfiction sex education books get removed from these kids, and as I see my kids enter those years, do I want them going to the internet to get their questions answered?” Ferrell continued. “Do I want them to go to an ill-informed friend? Do I want them going to a book that’s been carefully selected by a professional to provide them that information? I would choose the latter every single time.”

What happens now?

Free speech organizations including the Foundation for Individual Rights and Expression (FIRE) and PEN America have written to Florida school districts to alert them of the ruling and urge them to return books to shelves. Even so, Ferrell said that districts have been slow to do so.

“What we’re seeing from the school board, though, is that they’re taking their direction from the state,” Ferrell explained. “The state has said, ‘Do not do anything, we are appealing this. We expect it to stay, do not put books back.’ And unfortunately in a lot of these districts, they have gotten rid of the books already.”

When asked what kind of message the state’s promise to appeal sends to parents, educators and students in Florida, Ferrell responded succinctly: “It’s about control.

“You start here with ‘protect the children,’ and being able to limit and dictate what is appropriate in this public space, and once you can limit this public space then you can expand to the next public space,” Ferrell continued. “All of a sudden, we get people to accept that in the free state of Florida that it’s perfectly fine to have the government come in and tell us what’s appropriate and then dictate that and limit access to viewpoints.”

“I think that there’s a lot of political power in creating fear, and they’ve managed to build a very receptive base by pandering this story that there’s pornography in our schools and we need them to save us from it,” Tray added.

While the State of Florida has filed its notice to appeal Judge Mendoza’s ruling, individual school districts in Florida are given the choice to join the state in appealing, or stand by the court’s finding.

Ferrell stated that she fears that if districts decide to appeal along with the state, then they signal their disregard for Florida students’ First Amendment rights: “That’s a huge concern, regardless of what political leanings you have.”